Automate Reporting with Generated Changelogs

08 Nov 2020 . . Comments

The Problem

A release just went out this morning and your colleague just came back from holiday. A large bug surfaces on production and a QA asks, “What’s the cause?”. We look at the commits and find the associated ticket. The commit is in the release, but the ticket was never tested, tagged, or put into the release notes. Humans make mistakes far too often. I’ve seen too much code go to production without proper tagging.

A Solution

How do resolve this issue and ensure it doesn’t happen again?:

- Use app-specific semantic versioning [https://semver.org/) to reduce decision-making and complexity

- Automate the release notes with Changelogs

- Keep the changes and tags visible to all stakeholders not just developers

Will these solutions prevent all mistakes? No. These solutions simply provide the rest of your team with more accurate and reliable information relevant to the release. I believe the release process should be less ‘doing’ and more ‘checking’. I want to reduce the amount of work it takes to ‘create’ a release and just ship code. I would like to eliminate all sources of human error, so if I go on holiday I can confidently know tickets won’t be missed and left out. These solutions in turn…

Remove the following tasks from the process:

- Manually tagging or updating JIRA tickets

- Writing up a confluence document or another release ticket.

- Inconsistent human decision-making on versions - whether your version is 6.5.1 or 6.6.0

In this article, I will dig deep into each of the 3 solutions above and even discuss some bits to get started on the implementation.

The goal isn’t to entirely automate your release process, rather standardize it and make it consistent for all members in your team.

Ideally, I’d like anyone on the team to easily identify issues in a release without having to go to the developer who implemented the feature.

We should be able to ship code without the ‘coder’ there and be confident in their releases.

Semantic versioning

When working on a piece of code, I often find that I am working on one of the following:

- bugfix: a fix to an existing piece of software that has an issue - results in a patch version increment

- feature: a new feature implemented in a backward-compatible way - results in a minor version increment

- refactor: an update to existing software or improvement that doesn’t change behavior - minor version increment

- test: writing missing tests for software

- chore: a change to internal dev like infrastructure or productivity tools

A release is an amalgamation of these. With this soup of commits, it’s incredibly difficult to spot breaking changes or decide what is the next release version.

Implicitly, I think through the following:

- Were there any breaking changes in my release?

- Are there major feature changes or only bug fixes?

- How would this refactor be classified; how do I let the team know?

However, I cannot accurately answer these questions without the following information on each code change:

- Whether it’s a breaking change - how it breaks

- What type of change: bugfix, feature, refactor, etc

- Where the change was made, the scope

- Description of the change

- What JIRA ticket does it relate to

So, I first need to standardize my commits to get this information.

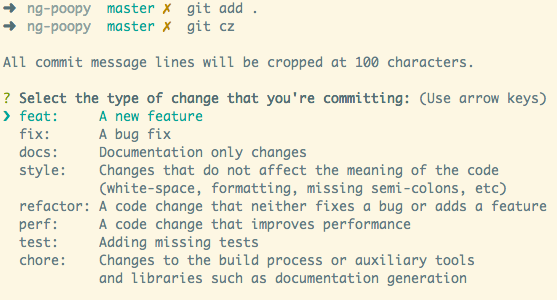

I get a tool (Commitizen) that asks for this information like below

It then adds that information to the commit like so:

Feature

feat(index.js): hello world implementation

#TEAM-101

Bugfix

fix(index.js): fix Hello World copy

fix #TEAM-102

Now, I have all the information needed to decide the release. I can take a list of changes and create a version.

If I give this list to someone else, they may give it a different version since they may miss a breaking change in scrolling through the commits.

Instead, we can version automatically using semantic versioning and thus the versioning will be consistent regardless of who runs a release.

What is Semantic versioning?

Semantic versioning automatically versions a group of changes based on a particular set of rules. I can generate a version automatically with the information provided above by the commits.

How is this done? It goes through the commits and checks for the biggest change and increments the release. If it’s only a group of bugfixes, it is likely to only increment by 0.0.1. If it’s a mixture like above, the version will be incremented by 0.1.0. And if it’s a full-on breaking change or new system an entire version will be incremented (1.0.0).

This may be an oversimplification as versioning can be quite complex. I recommend starting with these basics and asking your development team the following:

- How often do we release and how many commits are in a release?

- When and where (what env) in our development lifecycle do we cut a version?

- Are there any extra company-specific validation processes that you need to consider?

In answering these questions, I can then decide when to version a release with semantic versioning.

In a completely automated development environment, every commit has a version. These can be smaller versions like alpha/beta versions or regular versions. However, if you are versioning and not releasing lots of commits this can get out of hand. I’d recommend switching to automated commits when your development lifecycle is automated and close to a full continuous delivery (almost every commit is a release). Once the cadence of development increases, you can further automate other processes.

Generating Changelogs for all stakeholders

When I create a new release, I have a semantic version but I should also share all the code changes with the rest of the team. I can automatically generate documentation from the detailed information provided in my code changes (commits) by semantic versioning. Simply running a release using one of the following of these libraries (standard-version / semantic-release) creates the following: https://github.com/evanjmg/changelog-example/blob/master/CHANGELOG.md

# Changelog

All notable changes to this project will be documented in this file. See [standard-version](https://github.com/conventional-changelog/standard-version) for commit guidelines.

## 1.1.0 (2020-11-08)

### Features

* **index.js:** hello world implementation ([84a478c](https://github.com/evanjmg/changelog-example/commit/84a478cca57635ccfb5d98e822d13c5f6b4b9c75)), closes [#TEAM-101](https://github.com/evanjmg/changelog-example/issues/TEAM-101)

### Bug Fixes

* **index.js:** fix Hello World copy ([d8af554](https://github.com/evanjmg/changelog-example/commit/d8af55417ee5d01db928c4435ca9ebf24d18af64)), closes [#TEAM-102](https://github.com/evanjmg/changelog-example/issues/TEAM-102)

This can be customized to link to JIRA tickets and also include filters etc. One can then run another script to copy this log over to your release ticket or document.

Code Hooks to Share Release Tags and Changelog

The last step is to share the tagged version and changes everywhere:

- Automatically Tag all related tickets accordingly

- Generate links to ticket lists of changes

These steps can be done in the CI or build system with JIRA hooks.

When I decide to make a release, I will make a release commit and it will update the changelog, add tags to all the tickets.

Then any member on your team can click a version and see an accurate list of changes in the release. No tickets will be missed because they aren’t tagged manually by anyone on the team.

The changelog can also be forwarded onto a release ticket if necessary. Users can see specific details of the release or one can just use the JIRA filter of the release to see the status of all

tickets in the release.

In future articles, I will go over specific implementations of this workflow. If you’re interested in a simple code example of what we discussed, please check out this git repo here: https://github.com/evanjmg/changelog-example

Learn how to implement this workflow in Part 2.